**This article will contain spoilers and very graphic images from the film. You’ve been warned if you have a weak stomach or haven’t seen the film

Some people claim that the atrocities we commit in our fiction are those inner desires which we cannot commit in our controlled civilization, so they’re expressed instead through our art. I don’t agree. I believe Heaven and Hell are one and the same. The soul belongs to Heaven and the body to Hell. – Jack

Films about serial killers, fictional or not, will always have an audience. It’s one of those macabre interests that lies dormant in the deep recesses, and by watching real crime shows, documentaries and/or feature films on the subject we get to stand witness to these disreputable people. We want to know what makes them tick.

The thing is, do we ever question the artists who create these characters and these types of films? Do we want to know what makes them tick?

The latest film to broach the subject is from the polarizing provocateur Lars von Trier, titled The House that Jack Built. Watching a von Trier film comes with its own stigma. He’s an auteur if ever there was one and he ebbs and flows between self-indulgence and cinematic genius. For the most part, you can either handle his movies or you can’t, and similarly, you either like the man or you don’t. The ones who can’t handle his movies usually don’t like him personally and they made up their minds long ago that he’s a pseudo-intellectual, pretentious filmmaker with a predilection for shock-and-awe, and they make their discordance known. The ones who can handle his films eagerly await his next offering because you never know which category it will fall into: self-indulgent or cinematic genius.

I happen to fall into the latter. I haven’t liked all of his films but I find something interesting in each of them, which is something to be valued. The people that hate his movies hold a grudge and refuse to acknowledge anything of worth in his work, which seems to be counterproductive to engaging with cinema.

Many of his films have been labeled misogynistic because his female characters typically have to endure some type of abuse and/or degradation, especially the films with female protagonists (Dogville, Dancer in the Dark, Breaking the Waves). The fact that he has had sexual harassment accusations against him and his production company only fuels this fire. Not to mention, it’s mostly women on the receiving end of Jack’s grisly hobby in this film.

The House That Jack Built is an amalgam of everything written about Lars von Trier and his films. It’s messy, brilliant, self-indulgent, disturbing, stylistic, sadistic, misogynistic, philosophical, pseudo-intellectual, and often times beautiful and disgusting all at once. All of these terms, in one way or another, apply to the titular character, Jack (played perfectly by Matt Dillon). This is no accident; the film imbues all these adjectives upon itself.

The central theme is the nature of art and the dichotomy of body and soul, with a sub-textual argument about gender in a #metoo world. Jack is a serial killer who sees himself as an artist, often composing his murders to conform to some artistic notion, and he uses many different metaphors to explain his point. Considering film is von Trier’s chosen art, we can deduce that this comparison is von Trier’s own argument for the artistry of some of his more profane films. Jack goes to great lengths to argue for the value and beauty of horrific images and acts, and this film is von Trier’s way of pleading for justice.

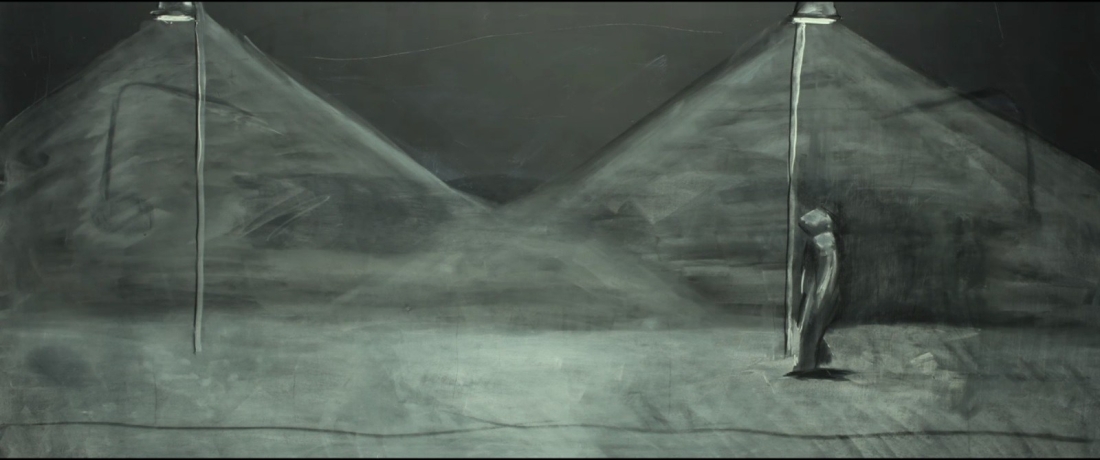

Jack is a narrator along with his guide, “Verge”, or the Roman poet Virgil (Bruno Ganz), as Jack’s soul is being escorted through hell, a la Dante’s “Inferno” (see images above). In the epic poem, Dante refers to hell as the “realm … of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen”.

Jack and Virgil engage in a dialogue about Jack’s life and his work, both of which certainly constitute a trip to hell by Dante’s definition. But, the conversation between them also represents the self-doubt, arguments, compulsions, and insecurities von Trier feels about his own films. Jack and Virgil ruminate on many subjects, with each offering their own philosophies across a broad spectrum of topics. Whenever Jack offers a validation of his argument, Virgil dismisses it with a poignant counterpoint, and vice-versa, and it’s hard to ignore the meta-textual commentary at play.

I’ll start with an example:

The above images represent one of Jack’s metaphors regarding compulsion, this one using the effects of light and shadow. The metaphor goes: when a person stands directly under a street lamp, their shadow is at its smallest but also at its darkest, or most dense. As they walk away from the light, their shadow increases in size in front of them, but the density of the shadow decreases. Jack likens this to a cycle of suffering and elation through compulsory action. The figure standing underneath the street lamp (Fig 1) is him when he has killed someone. He feels euphoric, but as time passes and he moves away from the street lamp, his euphoria decreases, much like the density of the shadow. As the figure moves away from the first street lamp and gets closer to the next street lamp, another shadow grows behind (Fig 2), this one representing a growing pain and desire to kill again. The closer the figure gets to the second street lamp, the less dense the first shadow becomes and the second shadow behind him intensifies. This signals his pain and desire to kill is escalating. Just before the figure gets to the second street lamp, the first shadow (euphoria) is nearly gone and the second shadow (pain, compulsion) is becoming more and more dense. This feeling can only be satiated by killing again, and this is represented by the figure standing directly under the second street lamp with the shadow at its most dense again (Fig 3).

Virgil dismisses this metaphor as the “addict’s tale of woe”, as it can be applied to any addiction, such as alcoholism, thus nullifying Jack’s justification. This is von Trier arguing for and against himself and his destructive compulsions. He validates their presence, then brushes them away as merely an excuse.

Von Trier uses many of these self-reflexive instruments throughout the film. I’m referring to those elements outside of the film, itself, juxtaposed within the narrative framework. These elements remove the viewer from the plot and reflect upon the nature of the film. Take the images below:

He begins with the image of the woman in Incident #1 (Uma Thurman) after Jack slams her face with a tire jack. Her face is mangled and bleeding. This image subtly fades into an image of a painting with similar imagery. For a few frames the dead woman is transposed over the painting, but as the woman fades away we can see that the image is that of a disfigured face, a painting entitled “Head of a Woman” by cubist artist Juan Gris.

By stepping back from the narrative of the film to show its relation to things outside the film, von Trier forces us to ponder: Who is to say that one is art and the other is not? As an audience member you find yourself thinking about this question and reflecting on the film, itself, instead of merely watching the action.

This is certainly not a new method and it has been used in countless films before this. The purpose is to pull the viewer back from the film and cause engagement and active participation.

Here’s another example:

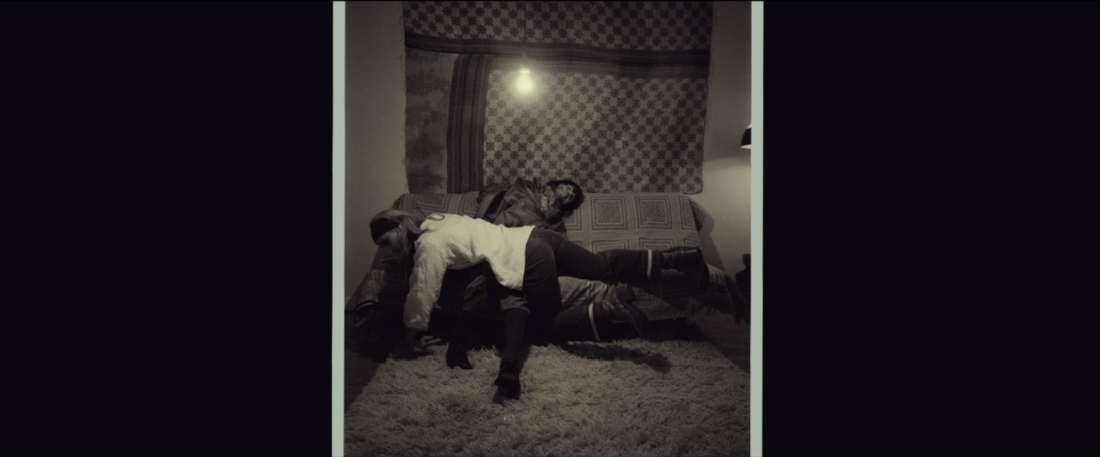

Jack has a hobby of taking photos of his victims with an old style camera he’s had since he was a child. This could be said to be the purpose of the kill and Jack’s real artistry. He photographs the dead body in various postures, sometimes posing them with some other deceased victims he keeps in his walk-in freezer. Take a look at this screen-cap:

Jack does this partially to humor himself, but he goes on to illustrate his preference of looking at the negative of the photograph, as in the picture below:

Von Trier uses this idea of the negative as a way of explaining the art in the, in this case, literal negative. Often his films are about negative subject matter and feature grisly, bare imagery photographed with a hand-held camera. They feel more real and grounded because of his use of natural light, natural sound, and his predilection towards hand-held camera work. By keeping the images grounded in reality and focusing on the negative themes, he challenges the viewer to see the art.

Jack is doing the same. He speaks of being fascinated by how the light appears when you look at the negative of a photograph, or as he calls it, “the inner demonic quality of the light; the dark light”.

This metaphor of light and darkness becomes the center of the argument. Von Trier makes it clear his interest is in the negative and there is nothing less artistic about that. He sees just as much beauty in the dark as there is in the light. This duality is explored throughout the film, which makes the argument seem to be, well, black and white. It would seem that there are only two camps when it comes to this type of view. Is there no room for gray area?

Along these lines, Jack speaks of the duality of being as well. In a discussion of body and soul, Jack holds the view that the soul belongs to heaven while the body belongs to hell, as stated in the quote at the beginning of this article. So, again, we see this black and white difference; the whole of the body represents one space while the totality of the soul belongs to the other. Jack’s use of the human body to create his art is a manifestation of this view. The body is not something sacred; it is a hellish vessel, or material. By photographing the lifeless body, he makes art out of something evil.

Jack does take it a step further regarding decomposition and its ability to create art. He recounts how certain grapes in Germany go through a process of decomposition as a means of creating a better wine. Jack stakes claim that through the destruction of structures (grapes, the body) there can be art, a claim which is followed by images of the Holocaust and other tragedies. He refers to disreputable tyrants, such as Hitler, as icons. Take the quote below:

As disinclined as the world is to acknowledge the beauty of decay it’s just as disinclined to give credit to those… no, credit to us, who create the real icons of this planet. We are deemed the ultimate evil. All the icons that have had and always will have an impact in the world are for me extravagant art.

Jack refers to this decomposition as “the Noble Rot”.

To this claim, Virgil scoffs in utter disgust and says he has never escorted a more depraved soul than Jack through the circles of hell. The venom in Virgil’s retort is a boiling point for one of our narrators. If Jack is a manifestation of Lars, and the films he has made are represented by the images and acts depicted in this film, then Virgil is the opposition screaming in von Trier’s ear. Von Trier, himself, got into hot water at Cannes in 2011 when he said he empathized with Hitler during a press conference, which caused him to be deemed persona non grata until this past year’s festival.

The argument can be made that Virgil is the critic or just the critical side of Lars, himself. But, in this sense, would we believe that he wrestles with the notion that he believes he is, or others believe him to be, the antichrist? Or could he be satirizing his controversial comments from 2011? It makes sense that he has dealt with these demons before and has certainly been deemed this very term before; not to mention, he made a film titled Antichrist.

Getting back to “the Noble Rot”, we are shown another example of this through Jack’s morbid process for the usefulness of putrefaction. He uses different methods to get around rigor mortis in order to “stage” the body in a certain manner, such as in taxidermy. He uses wires, tape, and other means to place the body in a position he wants. In this way, he makes them look alive, or, if you will, they would represent the negative of their normal selves, such as in the grisly image below.

Now, do we see the art in this image? The vast majority will feel repulsion. Is it possible for Lars von Trier to put this image into a film while arguing for the artistic merit of it? He has already made his claim for the beauty of the “inner demonic quality”, and of the “dark light”. The self-reflexive nature of this film keeps you thinking about how far someone is willing to go to prove the grotesque is beautiful.

Indeed, when Jack first posits the notion of killing a family with children, as in the image above, Verge seethes, and Jack responds “Don’t look at the acts, look at the works”. The images are paramount in this argument, regardless of the actions taken to create it. To this claim Verge retorts “Don’t try to manipulate me. And with children, the most sensitive subject of all”.

So, here we have another self-reflexive term to chew on. He uses the word “subject”, almost as if Jack and Virgil are reflecting on artistic creations and not the reality of the narrative. When referring to a child in real life you wouldn’t use the term “subject”; it’s a literary term used in art, writing, film, etc. Subjects are the property of the artist, and in this moment Jack is the artist and Verge assumes the role of critic. Von Trier deliberately uses this terminology in order to frame his argument in the world of fiction, again, as the quote at the top illuminates.

To say the least, it would seem that von Trier is frustrated with his place in the film world. He makes films in a way that elicit an emotional reaction, a cinematic affectation, but he doesn’t seem to understand it. The rough sell is that he is explaining his art in very cut and dry terms. It’s untenable to say that there are only entirely negative and completely positive films, unless he has been battered by criticism in such a way that he felt it important to create this film and this character. This film is his way of explaining his art, but where does he actually fit in?

The relation between creator and creation can be explored through the character of Jack as he relates to von Trier. Part of Jack’s frustration goes back to his childhood. He explains that his dream as a child was to be an architect, but his mother made him go to school to be an engineer. During the 4th Incident in the film, Jack defines the difference between an architect and an engineer: “an engineer reads music; an architect plays it”. There is a possible hint of self-doubt within von Trier about him being an artist.

Or, he’s possibly commenting on the role of his worst enemy: the critic. Much of the negativity lobbed at those that write about films is that they criticize because they are unable to create art. Another way of putting it: a critic reads movies, a director creates them. I won’t necessarily explore that here, but the relationship between critics and Lars von Trier has been tenuous, at best, so it bears mentioning.

In the film Jack receives a sizable inheritance that facilitates the construction of his own dream house. Wanting to be an architect, he sets out to design the home himself. He

philosophizes on the importance of the material and stresses that the right material has a will, as if it were living. If you find the right material it will do the work for you. This personification of material leads us back to using the body as a material, as it is made of matter. Jack begins construction on his dream house and knocks it down to start over several times with different materials, no doubt a feeling every artist has felt when trying to create a work of art. How many times does an artist begin working and then scrap it for another material, or method? In the end Jack is a failed architect, and in a sense, a failed artist.

The metaphor of “the material” illuminates the trial of the artist: which material to use to tell my story, paint my picture, shoot my film, etc. Early in the film Jack tells Verge about how old cathedrals and churches used to be built with one kind of architectural design and they were built merely as strong structures, but as the world evolved they began to use new materials and designs to make bigger, stronger cathedrals and churches that allowed for them to serve an artistic purpose, not just functional one, and to allow more light to pass through the building.

If we apply this metaphor to art, we see a comparison of old modes of production versus updated media techniques. His inclusion of the term “light” strikes a chord. Allowing more light to pass through a work of art would bring to the surface that which lies in the dark. Jack waxes poetically saying, “The old cathedrals often have sublime artworks hidden away in the darkest corners for only God to see.” If art is the structure von Trier is referring to, then his theory would apply to old films that are perceived to have been made for one reason: entertainment. Film started out as a medium of amazement and early filmmakers made films because they could, not because it was art. But, as modes of production evolved, it became feasible to make bigger movies that allowed more “light” in.

Jack’s comment about hidden artworks implies that older films possessed these elements, but they didn’t have the techniques, or freedom, to cast light upon them. The term “light”, here, can be applied to the evolution of film and the freedom to present more textual elements in modern media. Von Trier creates films that shed more light upon particular themes; themes that would have been too taboo for film-goers many years ago. Could you picture a movie like this, or any of his other movies, coming out back in the 1930’s?

The other troubling notion von Trier either deliberately or accidentally contextualizes, or sheds light upon, revolves around gender and race. The cries of misogyny in his films has been an issue for years. The themes he has explored generally involve the trials of women. Dogville, Dancer in the Dark, Breaking the Waves, Antichrist, and

Nymphomaniac are a few of the major examples in his oeuvre. Men in his films are almost entirely horrible people, but they take it out on the female protagonists more times than not. Almost as if his films are an indictment of male behavior, and the female is the victim of the consequences.

Perhaps it’s easier to begin with a quote from Jack:

Why is it always the man’s fault? No matter where you go, it’s like you’re some sort of wandering guilty person without even having harmed a simple kitten. I actually get sad when I think about it. If one is so unfortunate as to have been born… male, then you’re also born guilty. Think of the injustice in that. Women are always the victims, right? And men, they’re always the criminals.

Now, is it irony that a white, male serial killer is making this statement about the “injustice” men have to face and how “unfortunate” he was to be born male? It’s possible that von Trier is being satirical; putting these words in the mouth of such a wretched creature could certainly be construed that way. But, considering the portrayal of women in his films, it might be better to conclude these words are his own.

If that’s the case, then von Trier sees himself as above all of the #MeToo politics. Bearing in mind the sexual misconduct accusations again him, this would seem to be the thinking of a narcissist. And, Jack is very much a narcissistic character; indeed, he nicknames himself “Mr. Sophistication”. Since we have already concluded that Jack is a manifestation of von Trier, then the narcissism is equally a trait of his creator. The name “Jack”, itself, carries a connotation of “every man”, as in “a Jack of all trades”. Because this mundane name was given to him at birth, it would make sense for a narcissist to come up with such a nickname. His bland birth name gives way to his more fitting, self-given moniker.

Along these lines, there are variances in character that seem to suggest that Matt Dillon is portraying several different characters under the name “Jack”, or at least an embodiment of white male-ness. In one Incident, he’s an bumbling neurotic with extreme OCD who fails to strangle his victim to death and has to strangle her again, and in another he’s as calm as Spring rain as he murders his family with a hunting rifle. It could be theorized that Jack is actually a mixture of stereotypes of serial killers, who are predominantly white and male.

There is a scene inter-cut into the narrative where Jack practices having emotion in a mirror. The mirror is surrounded by photographs of people emoting different feelings and he attempts to copy their facial expressions in order to seem emotional. He has to feign emotion because he is, in fact, no one. Or is he every white male? If he represents the twisted white male demographic, then this character can be construed as a bastard child of white, male privilege.

The character seems to be comfortably wealthy, but he’s not a self-made man. His wealth comes from an inheritance, which is almost the very definition privilege. But, not only is he privileged in a socio-economic way, his skin tone and gender seem to absolve him of any kind of suspicion.

In Incident #2, Jack murders a woman and hangs around for quite a while to make sure the house is clean. Eventually, a police car arrives and Jack is interrogated by the officer, all the while the body is wrapped up in a bag about 5 yards from them. While being questioned, Jack stumbles through his alibi and acts as strange and guilty as possible, even to the point of acting aggressive towards the police officer. Despite all this, the cop orders him to leave the scene without further questioning. In a bit of black humor, Jack drives away with the body dragging behind his van as David Bowie’s “Fame” plays over the scene.

During the entire drive from the scene of the murder, the body is leaving a blood trail (pictured above) all the way back to Jack’s warehouse where he stores his victims in a freezer. Jack sees this and looks perplexed, and clearly we can see this is not a very “sophisticated” killer.

But, what should ensue: a rain storm, effectively washing away the blood trail and illuminating the metaphor at play. Jack gives credit to the heavens for this miracle, stating he has a divine overseer and assumes the godly intervention is a sign his actions are protected. Von Trier does not necessarily make an argument for a God figure (the film has been criticized for its nihilistic tone), so should we assume the heavenly overseer is the societal blind-eye that has historically been kind to white males? It would appear to be an indictment of society for washing away the blood trails of those with privilege.

The same goes for later in the movie, in Incident #4, when Jack’s girlfriend seeks help from a police officer and the officer discredits her story because she has been drinking; though it could, presumably, be because she is a woman. Jack proceeds to taunt her: “Scream all you want, no one will help you”.

After Jack dismembers this victim, he walks back downstairs and sees the police car still in front of the building. He notices the officer is interrogating two people down the alley next to the building, and in a morbid act of narcissism, he deposits a body part from his victim on the police’s officer’s windshield and walks off. Of note here, the officer is questioning two black people in the alley, thus further illuminating that, not only is Jack free to do what he wants without repercussions due to his gender, he has the luck of being born white.

Von Trier uses stylistic elements to illustrate some of these themes as well, namely his use of the color red. Take the images below:

The stark use of red is noticeable in every scene, but not through post-production editing or color grading. Each red element is definable in each Incident, whether it’s the red tire jack, the red telephone wire, the red robe Jack wears, or the virility of the red van Jack drives.

When you look up the symbolism in the color red you get the following:

- RED – anger, passion, rage, desire, excitement, energy, speed, strength, power, heat, love, aggression, danger, fire, blood, war, violence

The color, itself, takes on a life of its own in this film. It’s not an accident that von Trier chose to have red highlights in each incident. His filmmaking style is known to be one of, if not the most, organic in film history (just take a look at the rules of the style he helped create, Dogme 95). Many of the adjectives that red symbolize are symbols of maleness. In this way, von Trier weaves gender into the subtext through his use of red.

One of the final images of the film is Jack and Virgil stopping their descent to peer out at a beautiful golden field, a representation of the Elysian fields. In Greek mythology, Elysium is paradise for the gods and immortals. And, in this single moment near the end of the journey, Jack sheds a tear. The creature who had to fake emotion and thought so little of others, displays perhaps the only real feeling of his entire life – self pity. Possibly, in this moment before coming to his final damnation, he experienced a sort of regret at what he made of his life.

All these elements put together offer up a smorgasbord of philosophies and neuroses. I would have to imagine taking a trip through Lars von Trier’s psyche is much like Jack and Virgil’s decent through hell.

In the end, there are plenty of conflicting ideologies and we are left with a house of corpses – the house that Jack (Lars) built. We all try to build our dream homes but rarely find the right materials to complete the project, often demolishing it several times in the process. At one point or another, our darkest deeds end up being the poured into the structure. I think that goes doubly for Lars von Trier, who’s spent several decades building his house. Whether through his own doing or that of society, it seems to have been very similar to that which Jack rendered.